★★★★★

The Victoria and Albert Museum in London is the world’s largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.27 million objects. But it is also known for its epic exhibitions, covering everything from musical theatre to Coco Chanel. Its current premier experience is DIVA, which celebrates the power and creativity of iconic performers, exploring and redefining the role of “diva” and how this has been subverted or embraced over time, across opera, stage, film, and popular music.

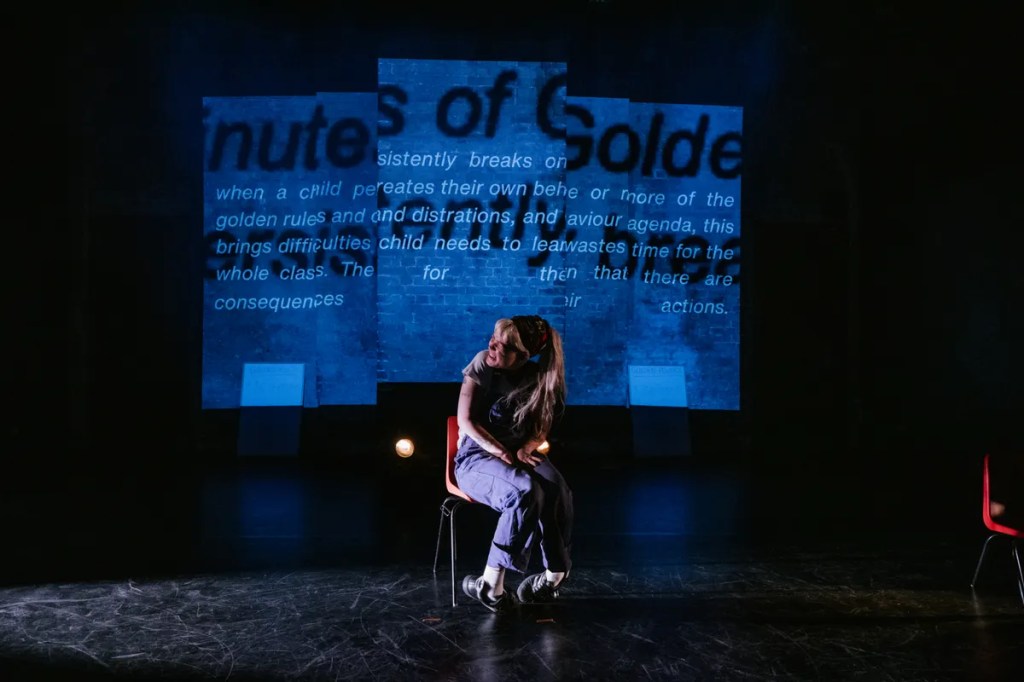

DIVA – which, unlike some other exhibitions at the V&A, is ticketed – is very much a theatrical experience, one so grand that it is fit for a diva. It sits in an enclosed space in a great hall, with moving images of various divas, from Marilyn Monroe to Kate Bush to to Beyoncé Knowles, projected on the top of the frighteningly high walls.

The experience could do with clearer signage. Most people arrive at the entrance not realising that you are supposed to pick up a headset at the other side of the hall.

The headset is the icing on top of this finely decorated exhibition. The headset plays a soundtrack; at every artefact, a different track is played – one corresponding to the diva in question.

The main event begins in sepulchral gloom. The exhibition is packed but, in the darkness, you feel almost alone – accompanied only by the soothing voice of Maria Callas (fittingly, ‘Costa Diva’). The space has been transformed into a theatre of sorts, with the house lights down as you prepare yourself for the drama.

“Diva” has gone on quite the process of semantic change. Derived from the Italian word for goddess, it was used for female performers when they first emerged in the 16th century (previously, most performers were male). It was not until the 19th century, however, where divas became a popular culture phenomenon, with singers such as Jenny Lind worshipped not only for their talent but also their charisma. In a full-circle moment, “diva” was not just a singer; it was a real-life goddess.

The exhibition takes a linear approach to divas, beginning with the operatic divas of the 1800s. Around the corner, there is a constellation of 20th century movie stars, with rivals Bette Davis and Joan Crawford pitted against each other.

The exhibition opens itself up to the global south, even honouring Lebanese singer Fairuz, one of the first Middle-Eastern women to make it as a music artist – and, indeed, a diva.

The exhibition really gets going on its top level, beginning with a section dedicated to Rihanna, who is as much a fashion icon as she is a music one, with her beauty brand, Fenty, making her a billionaire. The top level – act 2 of this theatrical experience – explores the heightened glamour of the contemporary diva. But it is not restrictive: it not only acknowledges irrefutable divas such as Cher and Tina Turner but also alternative artists such as Björk, contemporary artists such as Lizzo, less-mainstream modern divas like Janelle Monáe, queer divas like RuPaul, and even male divas, e.g. Prince and Elton John, the latter closing the exhibition.

Whilst the beginning of the exhibition hones in on “diva” in its traditional sense, it quickly becomes evident that the word has been interpreted in its widest sense – and the second act is a glorious exploration of the concept. One could ask if some of the modern divas acknowledged, e.g. Billie Eilish, have done enough to be crowned divas – but who gets to decide that? It is entirely subjective.

The second act, called “Reclaiming the Diva”, is a subtle acknowledgement of the semantic pejoration of “diva”. Originally a technical term, it quickly became a term of praise before became a slur of sorts, a nicer way of calling a woman a “bitch”.

But whilst other pejoratives have been reclaimed in recent years, divas never allowed that word to be awarded full slur status; they never stopped using it. Many female artists proudly called themselves “diva”: Eurythmics’ Annie Lennox called her debut studio album Diva, transgender Israeli singer Dana International won Eurovision in the UK with a song called ‘Diva’, and Beyoncé, the diva of today, released ‘Diva’ during her Sasha Fierce era.

The exhibition is strictly a celebration of divas but, behind the glitter, there is tragedy. Pairing Davis and Crawford is an acknowledgement of the ways in which women are pitted against each other. Lifelong enemies, the aged actresses agreed to star alongside each other in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? a bid to revive their careers, and as Ryan Murphy’s Feud explores, they did all they could to tear each other down and make themselves the star. The film was a huge hit, and Davis and Crawford were divas again, but were they happy?

Then there’s the UK’s own Marie Lloyd, a singer, actress and comedian who suffered from alcoholism and owed many debts. Against her doctor’s advice, she performed in London. Weak and unsteady, she fell over onstage, with the audience believing that her erratic behaviour was part of the act. Three days later, she was taken ill onstage and was later found in her dressing room, crippled with pain, complaining of stomach cramps. She returned home that evening, where she died of heart and kidney failure, aged just 52. Her £7,334 estate helped pay off her debts. More than 50,000 people attended her funeral.

But a diva never dies – and if she, like a star, begins to fade away, she can easily be revived, in exhibitions like this one.

DIVA runs at the V&A until April 10.

Photo: V&A