★★★★★

Following two sell-out runs at Sheffield Crucible, and a London debut at the National Theatre last year, the critically-acclaimed musical Standing at the Sky’s Edge has now opened in the West End.

The musical has a book by Sheffield’s own Chris Bush. A jukebox musical of sorts, it has music and lyrics by fellow Sheffielder Richard Hawley. It takes its name from his album of the same name, though it only uses said album’s title song, with most of the remaining songs taken from other albums. All of Hawley’s albums obliquely refer to an area of Sheffield, with this album referring to Skye Edge, which was formerly known for its crime-ridden estates but was largely redeveloped in the 2000s.

Standing at the Sky’s Edge has a linear narrative but it is set in three different time periods, with lots of back-and-forthing – and sometimes, two or even all three stories are performed at once. It explores the lives of three sets of people living in the same flat on the estate, so the scenes where characters from three different periods are seen in the same flat, at the same time, references the history of the flat (and the wider estate) and how much it has changed (for better or worse, depending who you ask, and when).

The characters in the past, shown to us in their present, are now like ghosts, haunting the estate which has become unrecognisable. The estate has changed, and new people have moved in, but the memories of former residents can never be replaced; their lives and stories have informed the present – and this is especially noticeable when the timelines coalesce and contrast.

In the late 1960s, Harry (Joel Harper-Jackson, who offers a devastating performance) and Rose (original cast-member and West End favourite Rachael Wooding, delightful as always) move into the then-new estate, a sanctuary away from the slums they grew up in. Their lives are pretty ordinary – they work, they have a child – until the 70s, when Margaret Thatcher (unnamed, like Voldemort) gets into power and the lives and livelihoods of working-class Britons, especially Northerners, are ruined. Harry takes it especially hard – and he takes it out on Rose (an intersectional exploration of class and gender).

In the late 1980s, a trio of Liberian refugees – siblings Grace (a powerful Sharlene Hector) and George (a charming Baker Mukasa), and their niece, Joy (whilst I had been looking forward to seeing Elizabeth Ayodele onstage again, terrific understudy Mya Fox-Scott was the emotional heart of the show) – move into the flat. The estate is no longer the haven it once was, and the Black refugee family unsurprisingly experience racism and hostility, but Joy soon falls in love with an English boy, Jimmy (Samuel Jordan, superb). The siblings eventually leave the flat, Jimmy moves in, and the couple have a daughter.

In the 2010s, Poppy, a posh lesbian Londoner – played to perfection by Olivier nominee Laura Pit-Pulford – moves into the refurbished flat, the estate now gentrified, the natives forced out of their own homes. Escaping her own past, she attempts to find a semblance of solace in the redeveloped estate. At work, she befriends Marcus (an amazing Alastair Natkiel) – both of them are gays that pass, resulting in the other thinking that they are being hit on and worrying how to let the other down!

Poppy’s snobbish parents, deliciously played by Adam Price and Nicola Sloane, are the bridge to her privileged life down south: Poppy can shake neither her privilege nor her past. Indeed, it is not long before her Scouse ex, the notorious Nikki (WhatsOnStage and The Stage Debut Awards nominee Lauryn Redding is sensational), finds her, and Poppy is forced to reckon with her identity.

Poppy’s realtor, Connie (Mel Lowe), is the link between the three different time periods, though her connection is not revealed until later on – but their role as an occasional narrator suggests that Connie is more than just a realtor and has a deeper connection to the estate.

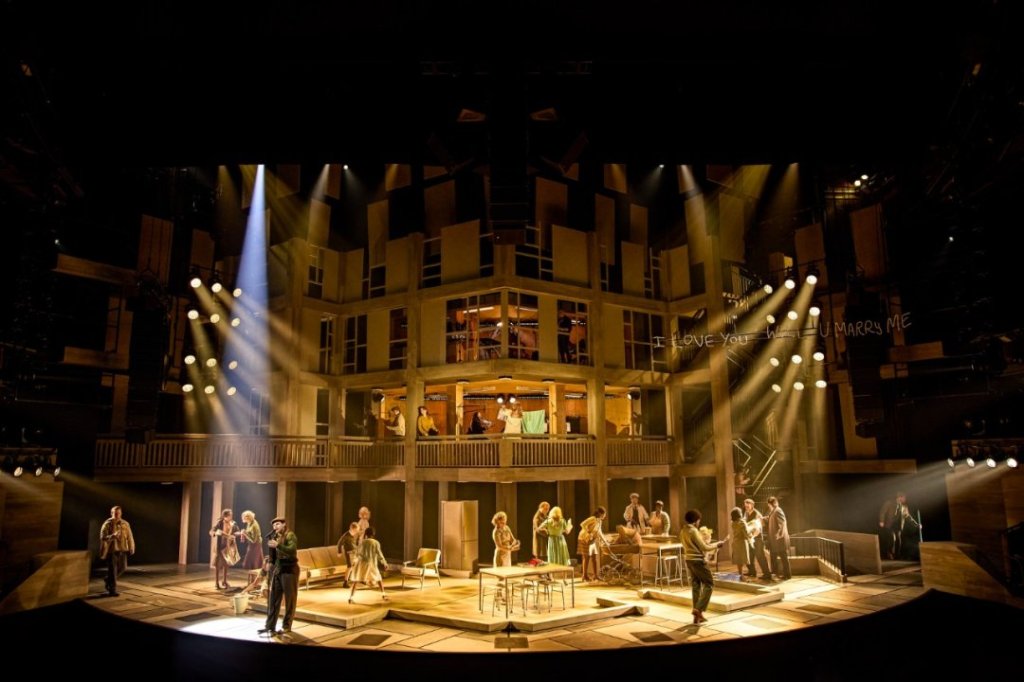

Ben Stones’ superb static set, built to look like the titular estate (complete with the iconic “I love you will U marry me” graffiti in neon lights), with its brutalist architecture, contrasts nicely with the opulence of the Gillian Lynne Theatre. The seats circle around the stage, entrapping the action in our midst, turning us from spectators to voyeurs. The audience – predominantly middle-class southerners – are confronted with the harsh realities of working-class Northern life, especially during the Thatcher years.

The production first played at the intimate Crucible and then the cavernous Olivier Theatre (at the National Theatre). The wide but warm Gillian Lynne Theatre seems to be the perfect in-between, in which the audience feel involved but there is a degree of separation, for this is not our story (this is why the intimate setting probably worked better in Sheffield).

The multiple timelines, with each timeline seeing years pass by in seconds, are never confusing. There are three blocks that lower from above, each with a digital clock. They are used at the beginning, establishing each timeline, and then on a few other occasions, for multiple reasons: to signify time passing by; to keep things from getting too confusing; or to parallel the timelines.

This is especially effective when each set of people are seen on an election night won by the Tories: Thatcher coming to power in 1979, replacing a weak Labour government; John Major winning his first election in 1992, when many thought Labour would return to power; and 2017, the first election since Brexit (which Nikki, herself a working-class Northerner, reminds Poppy that the residents voted her – signifying a snobbery even amongst working-class Northerners).

The musical is unashamedly political; it is not afraid to tell the majority middle-class Southern audience how Thatcher and Tory Prime Ministers since have terrorised the North.

The musical has one of the most epic ensemble casts ever seen in theatre, with every actor, even those in smaller roles, shining bright under the stage lights.

But the star of the show is the marvellous music, with Bush using Hawley’s rich storytelling to enhance her own jam-packed story(ies). The band sit in the set (on the balcony and in the flat above), rendering the songs characters of their own (in fact, some songs are like stories within an overarching narrative). At one point, a character thanks the band for their romantic melody, blurring the lines between fact and fiction, for this is a made-up story based on reality.

Most people are unfamiliar with the splendid songs in the musical so it does not feel like a jukebox musical; many people will presume that Hawley wrote original songs for the show. The creatives certainly had an easier job with this jukebox musical: there were no must-use songs; they could use any song they wanted, and Hawley’s catalogue is musically and thematically diverse.

But one cannot deny the creatives’ skill in selecting the best songs for the play, using each song to enhance and/or further the story. Sometimes the songs feel like plays-within-a-play, especially the title song, the Act 2 opener which sees the actors breakaway from the main action and really bring the estate to life, as they sing about unseen characters – who could be represented by some of the nameless individuals lurking in the background of several scenes.

The first few scenes of Act 2, consisting of ballads, nicely contrast the commanding end to the first act – but it is not long until the pace picks up, aided by Hawley’s songs, which get rockier as the act goes on.

Hawley, himself, said that he gets too much credit for this musical, for he wrote the songs for another purpose; the creatives put them together to create a striking story. Indeed, praise must go to orchestrator, arranger and originating music supervisor Tom Deering, who has refashioned the songs into majestic musical numbers, aided by sound designer Bobby Aitken.

Under Robert Hastie’s direction, the stage is sometimes littered with residents, and ghosts from the estate’s past, roaming the streets, weaving in and out of columns, and dancing along silently. Mark Henderson’s gorgeous lighting silhouettes them, giving them a spectral form.

The large cast means a lot of costumes (Stones), all of which are location and period-appropriate – and some of them are rather gorgeous.

Lynne Page’s contemporary choreography captures every emotion onstage, or heard in the music and lyrics. On a couple of occasions, it is perhaps a little too stylised for a play which can feel like kitchen sink realism, albeit on a larger scale, but it never feels like too much; the dancing speaks as loudly as the spoken words.

On a couple of occasions, the production becomes a little immersive, with actors roaming the pathway in between the stalls, at one point dancing romantically, as well as in the circle. At the end of Act 1, actors in the circle litter the stalls (with literal litter), as actors on the stage’s balcony do the same on “residents” below. They create an in-the-round space, with the audience trapped in the action, as the actors talk directly to us, confronting our voyeurism.

A love-letter to Sheffield, it is crystal clear that this story is the work of proud and patriotic Sheffielders. Bush explores an abundance of issues relating to Sheffield – and sometimes working-class Northerners more broadly – and her knowledge of the titular estate is abundant.

However, whilst the story is focused on Skye Edge, many of the themes are universal – and in some ways, the estate is microcosmic for wider British society and how much it has evolved (or regressed – or both) over the years.

But Bush makes sure that it is the individual characters, rather than the themes and issues, that are front-and-centre: we see how individuals are impacted by the politics at play – with the politics informing the story, rather than the story being written around the politics.

If you go to see anything in the West End this year, see this.

Standing at the Sky’s Edge is currently running at the Gillian Lynne Theatre until August 3.

Photo: Brinkhoff Mögenburg