★★★☆☆

Chichester Festival Theatre have revived Coram Boy, Helen Edmundson’s FRSL play-with-music based on the children’s novel of the same name, which was written by Jamila Gavin FRSL – who was recently, finally, awarded an MBE. Following its run at CFT, the play has transferred to the Lowry.

Coram Boy takes place in the eighteenth century. The benevolent Thomas Coram has recently opened a Foundling Hospital in London called the “Coram Hospital for Deserted Children”. Unscrupulous men, known as “Coram men”, take advantage of the situation by promising desperate mothers to take their unwanted children to the hospital for a fee – but ultimately doing away with the infants.

The book has two parts, set in 1741 and 1750 respectively – and the play follows this separation with its two acts. The first part centres around Alexander, a wealthy young man who gives up his money to follow his dream, and Aaron, a boy raised in the Coram Hospital. Both are connected to the mysterious Coram Man and his son, Meshak. The second part focuses on two orphans: Toby, saved from an African slave ship; and Aaron, the deserted son of the heir to an estate, as their lives become closely involved with this true and tragic episode of British social history.

It’s tricky even trying to describe the bulging plot – and director Anna Ledwich, herself, sometimes struggles to tie everything together. The pacing is inevitably inconsistent. It’s a long play – almost three hours – but it seems like not enough time to get through everything and give it the attention it deserves. There is so much going on, especially in the second act, that it can become a little difficult to process everything, with some dramatic moments going by unnoticed.

As a novel, I can imagine it being a real page-turner, but as a play, it can be difficult to remain invested and interested in everything going on. It’s certainly a better narrative than it is a drama.

The most interesting plot point – infanticide – feels a bit secondary, though each scene is gripping.

Relationships – father and son, friends, etc. – are explored and performed very well. There is, however, an uncomfortable scene where Alexander and Melissa, both minors, have sex. Melissa sits atop Alexander and moves up and down. We did not need to see teenagers having sex; it was clear where things were going.

The second act is definitely more interesting than the first. As a South Asian, it had surprised me that a British-Indian had written such a White story – with a focus on the aristocratic class – but there are some interesting class politics (and class during Victorian times was more rigid and not too unlike the Indian cast system), and the second act explores Britain’s involvement with slavery.

Indeed, the play grapples with various themes and ideas, ostensibly relating to Victorian society but also remaining relevant today – but few are given the attention and nourishment they deserve.

Late in the second act comes a gripping scene, in which the Ashbrooks realise that their loyal housekeeper, Mrs Lynch (Jo McInnes – steely and sublime), is a criminal involved with the Coram scheme. They blast her for making money on the suffering of others. Lynch accusingly strikes back: “All wealth is built on the suffering of others” – a thought-provoking idea which goes by unexplored.

Lynch is morally dubious, and this scene breaks down the hero/villain binary, but by the end of the scene, the Ashbrooks are back to being the good guys. Lynch then goes to warn the villainous Otis Gardner that the Ashbooks are on to him, solidifying her place as a villain – though one might see this as her solidly going against her insufferable, aristocratic employers and siding with a self-made man (even if he has made his money on the suffering of others – by murdering babies!).

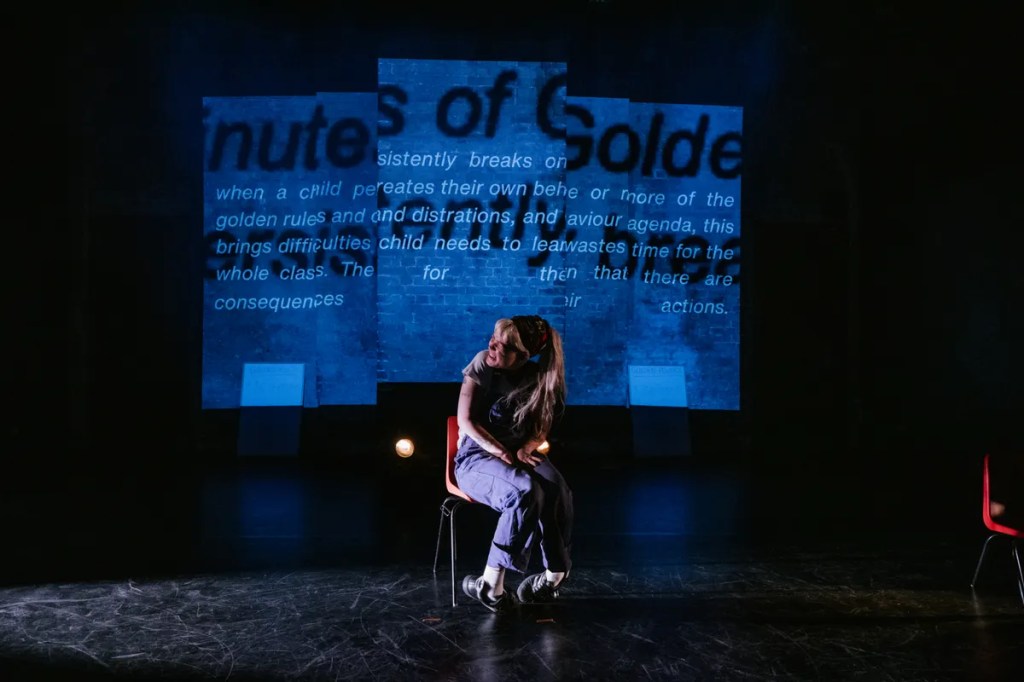

The production is stunning. Simon Highlett’s two-tiered set, which doubles as a cathedral and a stately home – but also transforms into other locations with the help of Emma Chapman’s dramatic lighting – is striking. It’s static but there are some moveable elements, including several chandeliers. The raised stage moves – this is utilised very successfully on one occasion, with the characters drifting forwards dramatically.

There are some nice stylised elements and moments of expressionism (including slow-motion movement) that stand out in a naturalistic play that is otherwise played quite straight – though the use of lighting and sound render them melodramatic and make them feel a bit out-of-place.

The set is surrounded by a black curtain, and the lighting remains dim. It’s as if the action takes place in perpetual darkness – or, perhaps, the abyss. It’s very effective. But for a play that runs almost three hours, it can feel a bit tiresome – and might just put you to sleep.

An interesting creative decision is casting female actors in the roles of the young boys. I tried thinking of reasons for this. Are the creatives trying to parallel the plight of women and children in Victorian society? The infantilisation of women. But that’s not really what the story is about – and it is made quite clear that Sir Ashbrook has control over Lady Ashbrook; one need not enhance this meta-dramatically Thus, I am probably giving the creatives too much credit. The boys sing in a choir, and there is much talk about Alexander’s voice soon breaking, so perhaps girls were simply cast so that they could reach the high notes. Indeed, the older versions of the boys are played by male actors.

Adrian Sutton’s songs, hardly ear worms – they need not be – perfectly capture the vibe of the story, and they are sang wonderfully.

Coram Boy is a long play. I often say that nothing needs to be that long, yet almost 3 hours feels not long enough for such a meaty narrative – making the play feel a bit bloated and rushed.

Coram Boy runs at the Lowry (Lyric Theatre) until June 29.

Photo: Manuel Harlan