Opera North’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Benjamin Britten) is a visually inventive twist on the Shakespearean classic weighed down by the show’s nightmarishly immense text length and sometimes dreary score.

This opera adaptation of Shakespeare’s much-loved three-act play was created by Benjamin Britten. His opera compositions capture the mixture of whimsy and unease, the otherworldly and psychedelic fairy marches alongside the evocatively melodramatic human world.

Martin Duncan directed the show for Opera North’s original production, basing the story in the 60s, in which the opera was conceived, using the source material and placing it in an equally mind-boggling world of hippie tie-dye, minimalism and futuristic aesthetics.

The story explores the adjoining fairy and human worlds and the concepts of love, sex and passion. Fairy king Oberon (James Laing) orders his servant Puck (Daniel Abelson) to cast a love spell on queen Tytania (Daisy Brown) after a quarrel resulting in her falling for the Donkey-faced Nick Bottom (Henry Waddington). Oberon also interferes with the lives of four lovers as both Lysander (Peter Kirk) and Demetrius (James Newby) are obsessed with Hermia (Siân Griffiths), leaving Helena (Camilla Harris) heartbroken. One mistake later and the tables turn! Meanwhile a group of craftsmen worry about putting on a play for the Duke. It’s a random story, yet it has many nice ties, memorable moments, and parallels.

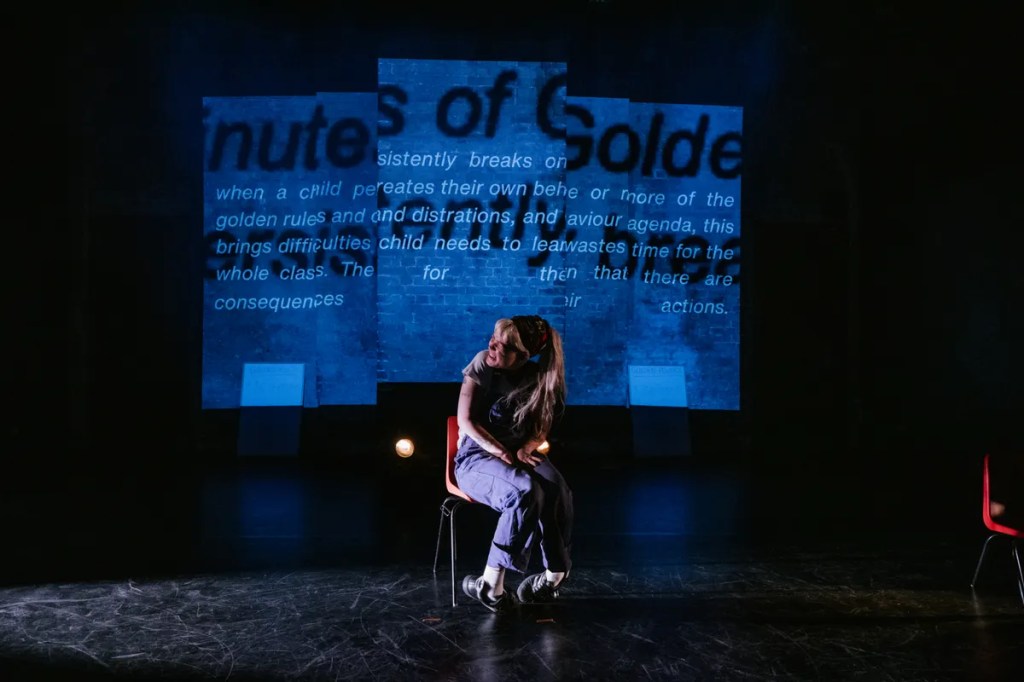

In a move from its traditionally floral woodland setting, we are given a world that lies somewhere between the alien and robotic. Translucent Perspex films are lifted and lowered as characters are revealed, silvery pleated curtains dress the set edges, and a string of bubble-like balloons flitter ominously as scenes change (lingering there for a tediously between scene transitions).

While I appreciated the fresh take on the set, I had mixed feelings on the end result. Sometimes the set felt mystical, hiding characters between veils and shrouding everything in this sense of mystery. Other times. the set reminded me of a strange bathroom, shower curtains draped around the corners, bubbles spilling from a non-existent bath, and often times feeling a little sparse and large for the human characters to fill (although pairing quite well with the fairy scenes).

Shining through the silvery set are Oberon and Tytania’s stunningly glitzy outfits – their heads cleaved helmet-like in shimmering fabrics and Oberon’s armour blinding the audience with its mirror ball effect – aesthetically pleasing but a tad too reflective for my taste. Similarly, while matching the eerieness, the Village of the Damned-inspired winged blonde identical fairies were also an odd choice, their choir sounded enchanting yet many of them looked drained (it was a late show after all).

Puck’s costume was nicely crafted with detailing accentuating his spine, prosthetic ears, spiky hair, and almost noodle-like thick hair coating his legs up to his blood red shorts. Abelson’s extremely physical performance involves crawling Gollum-like across the stage, rubbing up sympathetically to the controlling Oberon, twisting and contorting acrobatically, and comedically slapping his butt. His performance and dynamism on stage was one of the show’s strongest elements.

In contrast, the craftsmen of the play within a play subplot all had a variety of random costumes, one wearing an artistic beret and flannel, another wearing an old-fashioned waistcoat or a tuxedo, and the oddest clad in a black leather jacket with a baseball cap breaking the cohesion. I was often baffled by the stark contrast of the three groups with the futuristic shiny fairies, the hippie lovers (often in their underwear when the mischief heightens), and the randomly garbed artisans. Then even the tie-dye costumes are ditched for glittering cocktail dresses when the main lovers settle their quarrel and meet the Duke (perhaps a symbol that they have moved into reality outside the realm of the fantastical?). Here, it would have been better to keep that niche aesthetic for the supernatural realm rather than blur the lines further.

Musically speaking, the opera is as dreary as its pace with Shakespearean sonnets given in weirdly lengthy song form. Unlike all the operas I’ve seen so far, these songs lacked that punchy dynamism or emotional connection. While the cast sang their hearts out, there were a few musical arrangement choices that were inventive but distracting, i.e. the countertenor of Oberon or Puck anarchically singing some lines and speaking the majority of others. It left me craving more spoken word at points despite my love of the opera genre. While the music often reflects the tone of the situation, or the personalities of the characters, the added opera elements sometimes feel shoehorned into repetitive melodies with heavy exposition.

Additionally, the opera was weighed down by its decision to stick to the original lengthy three act s- poeticism that couldn’t be fully appreciated in operatic form and that often stalled the plot (although I loved the parallels between both worlds and the enriching mythology references). The main meat of the action occurs within act two. Act one is heavy in world building, tedious in its fact the best act. There’s a lot of comedy with Puck’s mischief, the hilarious flirtation between the now transformed Bottom and Tytania, and there’s the insulting retorts as Helena and Hermia fight over the fawning love-sick boys.

There’s something to be said about the lack of female agency in this particular tale as the women are completely obsessed with their beloved, but it is Shakespeare. Their witty retorts and frustration are at least engaging moments despite pining over true love (I’d love to see what a modern adaptation à la & Juliet would do to the piece).

Despite this, I must commend the female trio for their breathtakingly powerful singing. When the score allowed them to let loose, they blew me away with their vocal prowess, as did Kirk’s (Lysander) excitable and passionate solos, and Waddington’s (Bottom) mischievous low tones.

The action of act two feels refreshingly fast-paced, funny and entertaining, but this immediately lost within the third act and it’s drawn-out plot – something that can limit an opera in ways it wouldn’t during a play.

Shakespeare’s love of the play within a play returns again as the craftsmen act out Pyramus and Thisbe (a Romeo and Juliet lookalike) to the now regally dressed lovers and the duke, tying each branch of the story into a bow before also seeing the strangely reconciled fairy king and queen. While the section felt comedic, after so much content and having gotten past the main storyline, it failed to grip me as it should have. The comedy and drama fell flat despite the cast’s ardent delivery.

I often see opera as a night to be gripped by tragedy and emotion, maybe take in a few more comedic moments, and get lost in the action, but here that impactful feeling (whether due to the text or their adaptation of it into this form) felt rather placid. There were attempts at dynamic changes, interesting imagery, futuristic costuming, and yet the rest of the work was firmly planted in the past.

Saying this, it certainly doesn’t put me off operas that try something different and more exciting with their material. There’s so much potential in opera to use interesting imagery, modern stylings, and new interpretations. It just didn’t translate perfectly in this one instance. Had it been condensed and continued its inventiveness, I think more audience members would have been won over despite its quirks.

Ultimately, Opera North’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream sleepwalks through its overwhelmingly long runtime despite the stellar cast’s attempts to provide lively and engaging performances. It needed more time to decide where to go with its inventive aesthetic, a few alterations to liven up the score, and some way to balance these elements with the bloated Shakespearean text. It’s a dreamy-eyed interpretation but a slightly dreary execution.

Opera North’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Britten) tours the UK until November 20.

Photo: Richard H Smith