★★★☆☆

The modern classic Dancing at Lughnasa by Brian Friel, takes the stage as Elizabeth Newman’s first production of her inaugural season as Creative Director of Sheffield Theatres. The production finished its run in Sheffield in early October, and began in Manchester this week.

County Donegal, 1936. A story seen through a child’s eyes, retold through a man’s memory, Dancing at Lughnasa captures the antics, affection and quiet heartbreak of five sisters whose lives unfold in the wake of great cultural change.

Michael, now a grown man, narrates the performance in retrospect, telling the tale of his mother and aunts as they navigate the reverberations of the coming Industrial Revolution and the opening of a knitwear factory in their small town.

Their world is small yet vivid: green grass spills across the floor, creeping into the kitchen and beneath the stalls’ feet, while a golden, drum-like structure looms above the cottage. The Exchange feels magical, transformed into rural Ireland.

At the centre are the Mundy sisters, bound by love and frustration, yearning for connection and escape. The eldest sister, a teacher and de facto matriarch, faces the loss of her position while the family struggles to make ends meet, surviving on soda bread, herbs, a couple of eggs and homemade jam.

Their lives are marked by a blend of Catholicism and the distant echo of Ugandan spirituality brought home by Father Jack, newly returned and spiritually transformed after years abroad as a missionary. Themes of faith, desire and repression intertwine; sisterhood, lust, isolation ring through each exchange.

The sisters’ chemistry is remarkable, their interactions feeling intimate to watch.

Siobhán O’Kelly shines as Margaret – fiercely independent yet playful and warm – balancing moments of childish fun with young Michael, and antics with her sisters. Her performance anchors the production with emotional depth and vitality. This balances excellently with Natalie Radmall-Quirke’s portrayal as Kate, representing the taut length of string holding the family together, strained and contrarian to her sisters’ passions.

Frank Laverty gives a powerful performance as Father Jack, his mind drifting back and forth between his past and present, between Ireland and Uganda. His memory is fleeting, his perception of reality shifting. Laverty is intense, portraying Jack’s jaundiced, malaria-ridden initial appearance through to his quick-witted revitalisation – a man now closer to Ugandan spiritualism than his former Catholicism.

By contrast, Michael’s father, Gerry, feels somewhat underdeveloped. His dialogue circles rhythmically without ever fully grounding him in the same realism that defines the women and Father Jack, which slightly lessens the impact of his scenes. While I admired the intention behind Michael’s closing monologue – with the sisters swaying in response as the great drum lowered above them – the narration occasionally felt unnecessary. Michael’s presence, though heartfelt, lacked the vitality and immediacy of his female counterparts, whose interactions and energy brought the household so vividly to life.

The play’s most powerful moment arrives when the sisters dance together – a wild, electric release of pent-up emotion. They shriek, laugh, stamp and spin, utterly consumed by the rhythm and by each other’s energy. Even Kate joins in, dancing a stiff, joyful jig. It is an extraordinary sequence that captures their shared spirit and longing. I was left wishing the production had pushed further towards this ecstatic climax, which never quite arrived again.

Dancing at Lughnasa has intense moments of beauty, showing the deep connection between sisters, and how quick this can grow apart and change with culture and industrial change. Moments of this production grew weak with a lack of climax.

Dancing at Lughnasa offers moments of striking beauty, capturing the deep bond between sisters and how fragile that connection becomes amid cultural and industrial change. Yet at times, the production loses momentum, its emotional arc lacking the full climax it promises.

Dancing at Lughnasa runs at the Royal Exchange Theatre until November 9.

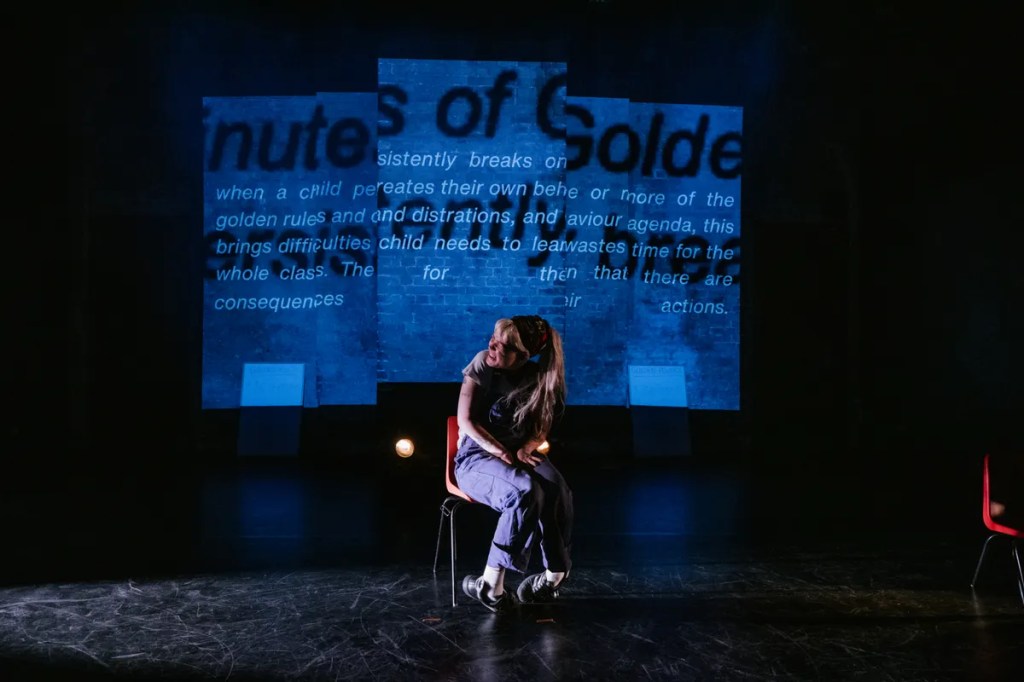

Photo: Johan Persson